Odd Voice Out

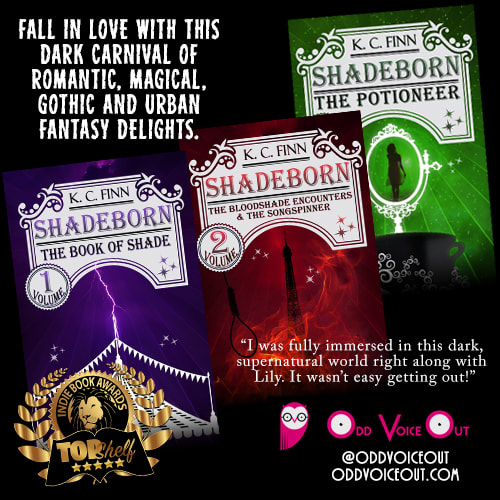

The World Of The Wish Preview11/28/2020 Coming to your e-readers in 2021, the fifth and final exciting instalment of the Shadeborn series, by K. C. Finn.The bright summer sun seemed unable to pick through the layer of silver clouds that always sat atop the hidden town of Pendle. But Lily Coltrane had no time for the sky or the shadepeople who walked freely on its cobbled streets. She had only one place to visit this day. Lily had been ushered through the musty, tumbling stacks of the booksmith’s shop by the ever-helpful Baines, but then the smiling old man had left her at the door to the back room. No words, no explanation. He knew she’d be back, just as Forrester had decreed, and that it would be when the time was right. Lily took a breath, staring at the old wooden door for a moment. She knocked softly, her knuckles quaking a little as they wrapped the heavy surface. The door was so thick that Forrester wouldn’t hear it if the shop was being robbed out here. So Lily placed her palms on the door, channelled a little extra strength into her veins by way of gravity magic, and opened the door to peer into her grandmother’s crowded little living space. The antiquated room was filled with a blinding white light, so vivid that Lily leapt towards it, suddenly on guard for some foul magic at play. But Forrester was sleeping peacefully in her rocking chair, and the bright white light had taken the form of a cloud. It emanated from the space around her grandmother’s head and, inside that pocket of light, figures were moving. The ancient shadewoman’s face was slack and soft. Forrester was deep in a dream, and Lily could see it. They moved in that translucent way that dreams sometimes did, where backgrounds lost their details and people blurred in and out of focus. Lily thought that she could make out an azure sky and brilliant red long-grass on the dream’s horizon, but the closer scene had deep, black clouds closing in on its edges. There was a figure in blue – or perhaps he was blue – who shimmered as he stood tall above a collection of other people. There was a boy who seemed to be made of words and a girl who looked like a ghost, and behind them stood an elegant figure whose head appeared to be silver. And at the front of the party, there was Novel. Lily was certain that she could see her beloved Lemarick in Forrester’s dream. His white hair shone atop his thin frame, a black suit making his arms and legs look long and spindly. Novel was facing the large blue figure at first, but he turned in a sweep of monochrome and seemed to gesture back towards the other people. Another figure, shorter and less slender, stepped forward. She had long, red hair that shone like the long-grass. Lily gulped hard at the image, trying not to see the resemblance to herself there. There was a flash in the dream, and the whole of the bright light shook within Forrester’s room. Lily watched in horror as the dream-Novel cast wild lightning into the darkening scene, and the boy of words and the ghost girl fell to the ground. The silver-headed man tried to fight against Novel’s attack, but he too was swallowed and struck by bolts from every direction. Then, there was only the large blue creature, Novel and the thing which looked like Lily. Novel cast again, and Lily fell to the ground too. He loomed over the supine figure. The girl who would never get back up. Lily cried out, and her voice echoed through the little room. “No!” Forrester awoke with a start, and the bright dream instantly vanished into nothingness. Lily cursed at once, desperate to see the dream world again and know its meaning, and the little old woman in the chair gave her a chiding tut. One of Lily’s hands snapped to rub the back of her neck, pushing away the clammy beads she found there. Forrester folded her little wrinkled hands, opening her eyes wide enough that her bright blue irises sparkled out from deep sockets. She waggled a finger skinny as a tree stick at Lily. “That’s no way to go. Cursing in front of your Granny.” “Sorry.” Lily brought her hands together at her handbag, clutching the straps and fidgeting there. Forrester had said the ‘G’ word already, and that made the opening of their conversation so much easier to broach. Lily took a breath before she started. “So, you knew? You knew I was a Schoonjans when I came to you earlier this year?” The ancient lady nodded, patting her knees. “I saw it in my dreams, a long time before you came to me, and I asked your Lemarick not to tell you at first. You had to be ready.” The mention of his name stung Lily deep in her heart, but she swallowed hard until the shaking feeling in her gut passed. “Your dreams. I saw them, just now. Are you saying that you can predict the future when you sleep?” Lily must have looked hopeful, for Forrester reached out for her granddaughter’s hands. She stepped closer to reach them, and they touched with warmth. Lily felt the old shade pat her palms gently. It was an oddly comforting sensation. But then Forrester heaved a little sigh. “Not all of it, sweet girl. I’m sure you already know that the future is changeable. But all shades have a little gift of prophecy in their dreams, and it does improve with age. You must have had that feeling, sometimes, that you have already dreamed something that’s happening now.” “Deja-vu.” The words left Lily’s lips softly as she nodded. Forrester patted her palms again. “That’s what the humans call it, dearie.” They broke hands, and the grandshade adjusted her silver nest of hair after her sleep. “Try not to heed my dreams, precious girl. They are mixed in with the addled imagination of a very old lady, after all.” Enjoyed this preview? Get your hands on the rest of the series and start your magical adventure with the Shadeborn today!

0 Comments

Jack Bumby Interview9/24/2020 Jack Bumby is a writer living and working in Greater Manchester. He studied Creative Writing at Edge Hill University, during which time he won the LoveSexTravelMusik competition organised by author Rodge Glass, with his short story ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice?’. Since leaving university, he has placed second in a scriptwriting competition at Tyldesley Little Theatre and self-published a collection of short stories with fellow writers, titled ‘The Torment of Thomas Farriner’. Currently, he is an avid reviewer and spends a lot of time contributing to his blog, ‘My Creative Ramblings’. He is working on a novel and has recently begun a Master's Degree in Creative Writing. In our interview discussing his distressing yet beautiful short story 'Imago', Jack talks us through his personal writing process. The themes of illness, hallucinations and uncertainty play a huge part in the intrigue of reading ‘Imago’. How did those themes come about? These sorts of things came about from the research I did around the disease. In the story, it’s an unnamed disease but was inspired by a real condition named ‘fatal familial insomnia’ (FFI). I read ‘The Family That Couldn’t Sleep’ by D.T. Max and found FFI to be just the most terrifying illness. It has a lot of symptoms, like hallucinations and delirium. A lot of the symptoms also mirror the things most of us experience in our teenage years; sexual issues, panic attacks, paranoia, stress, emotional ups and downs. Are you more of a meticulous plotter, or a seat-of-your-pants style writer? Plotting is something that can really stress me out if I focus on it! I remember reading a quote from Stephen King – in ‘On Writing’ I think – where he said that every story is a fossil. You have an initial idea, then it’s up to you to uncover, dig, and discover as you go along. Often you, the writer, don’t know where it’s going. You just keep digging and see where it takes you. That’s an idea that stuck with me. Whilst there has certainly been a surge forward in the representation of young gay men in YA literature, your story takes the sexual awakening element in a more mature and compassionate direction. How important was it to you to effectively and realistically portray this? In terms of concerns for a young adult, I think that sex and sexuality is usually at the forefront of these worries. It’d be doing a disservice to the young people currently experiencing these feelings to not treat it with respect and compassion, and to not talk about it plainly. So I wanted that to be one of the most important parts of the story. And this element was probably the part of the piece that required the most examination and redrafting. Primarily, I wanted to focus on the intimate and emotional side of his sexual experience. It’s a very human and necessary act, in the midst of all this stress and turmoil. It’s one of the few moments of light in an otherwise dark story, so it was vital that it felt real. The relationship between Charlie and his father lies at the heart of this story as a grounding force whilst other elements are spinning out of control. What was your process in creating this bond between father and son? That idea of the relationship being a ‘grounding force’ is exactly right. Charlie is dealing with a lot in the story, so I wanted that father/son relationship to initially be one of understanding and kindness. For example, his sexuality is a non-issue between them; his father just wants him to be safe. But as the story continues, I wanted to bring in this idea of an inevitable rift between them. Despite their best intentions, there are things they can’t talk about. These are ideas society has forced on them, namely that men don’t talk about their feelings, about what they’re going through. So I wanted the relationship to have this sort of tragic side to it as well – but their relationship needed to be strong for this to hit with the full emotional weight. There are a lot of different elements going on ‘Imago’ which makes it a very rich and complex read. How did you handle the balance of the plot with so much going on in Charlie’s life? For this, redrafting came through and saved the day. I mentioned before about how I write and just let the story unfold as I go along – but this way of working makes the redrafting process all the more crucial. You have to trim and cut to get the story down to the key elements. Charlie’s illness, his burgeoning sexuality, his father. Anything outside of that had to go. K.C. Finn at Odd Voice Out was so vital to this process too. And I think it’s integral, if you’re going to have a lot of elements in a story like this, that they all mean something to the overall piece. What does a typical writing session look like for you? For me, I work best with some noise. Coffee shops are great, and there’s an excellent co-working space in Manchester called ‘Ziferblat’ that has been a godsend. Also, I know it’s considered a bit of a writing sin in some circles, but I write best to music. Some people say music influences your writing, but for me, it’s a way to keep me focused. Without wishing to spoil the story for those who haven’t read it yet, the overall tone of ‘Imago’ is much darker than that of your typical YA tale. What made you choose this very effective alternative storytelling approach? ‘Imago’ covers some heavy subjects and one of my aims from the very start was to take them all seriously. Young people are dealing with some very serious things in their own lives, and in the tumultuous world around them, and I reckon we shouldn’t avoid discussing these things. I work with the idea that young people are much more attuned to these issues than people give them credit for. But again, there was that line. It had to serve the story. The darker elements are all there for a reason. What’s next for you as a writer? Next up, I’m aiming to finish my Creative Writing MA – you always have to be studying something, I reckon! On top of that, I’ll be hopefully working my way through my first novel and submitting to as many competitions as humanly possible. Sabah Carrim Interview8/29/2020 Sabah Carrim has authored two novels, namely Humeirah and Semi-Apes, both set in Mauritius where she was born. Her short stories have been shortlisted and published in various competitions organised internationally by Commonwealth Writers, Goethe Institute South Africa, and recently by the Bristol Short Story Prize. Her nonfiction was also a semi-finalist in the Gabriele Rico Challenge for Creative Nonfiction, and is scheduled for publication in an upcoming issue of Reed Magazine. Sabah was invited to be judge of the African Short Story Award, as well as to deliver the keynote speech on Cultural Stereotypes in African Literature at the African Writers Festival held in Nairobi in 2019. Sabah is also a law lecturer, and holds a PhD in Genocide Studies and Prevention, with a focus on the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge era. Here we discuss her delightful coming of age story 'Size of Rice', featured in our 'Odd Voices' short story collection.  You are one of the most experienced authors in our collection. How long have you been writing and what has been your proudest achievement so far?

I started writing when I was very young. But professionally, I started working on my first novel when I was 16, and then completed it later at 28. My proudest achievement so far has been a series of events last year where the short stories I wrote were shortlisted in various competitions across Africa, Europe, and the US. What does a typical writing session look like for you? I write poetry almost anywhere, because it can be done very quickly. If I work on a novel or a short story then I usually do it at home in my study, or in a noisy café—I like the movement around me, although I don’t like to take an active part in it. Once I am done, I usually spend hours looking at the work in the course of polishing it. And by this, I really mean hours. I can write a poem in twenty minutes but spend an entire day polishing it. How do you approach writing YA fiction with a teenage protagonist as opposed to writing fiction that’s about and aimed at adults? I try to recall memories of my teenagehood when I write YA fiction. I used to keep a diary where I would record my thoughts daily, and maybe because of that and a few reasons I may not entirely aware of, I can recollect those days very vividly. Writing for adults just means I can make direct and indirect references to the literature I read today, and introduce the more mature thoughts I have now compared to when I was a teenager who had many more questions than answers. Can you talk about residing and setting stories in Mauritius? What aspects of the island and its culture are you most keen to convey to readers from all over the world? In most of the stories I have written about Mauritius, I have dealt with my own experiences growing up there as a Muslim, and as a person of indian origin, and my main focus has been on decrying the superfluity of religion and culture that complicates our lives unnecessarily, and makes us lose focus on what I deem to be the bigger picture of everything else. How did you go about creating Binti’s distinctively neurotic voice? It was based on my own neuroses as a child growing up with a madrasa education where I was told that the hair on any part of my body should not be longer than a grain of rice. I remember how this and other similar teachings haunted me for days, especially because I tended to push the logic further, and end up wondering as Binti does in the story, what type of rice my teacher was referring to. Of course back then I didn’t realize that that would be good material for a short story. Do you think Muslim teens (and other religious youth) have a tendency to over-think their faith and worry about whether they are getting it right? Not necessarily. I realized with time that the reason those questions haunted me and not my other friends and classmates who were given the same teachings, was that they didn’t necessarily break their head over such matters. I think it’s only when one pushes the logic of all these teachings to the end that one realizes how nonsensical they are, but more often than not, parents and teachers are not equipped for such a challenge, and end up criticizing and humiliating the child or the student for asking so many questions. It’s rare that the hormonal and bodily changes of female puberty are portrayed in teen fiction. Do you think there’s a pressure on young girls not to talk about their growing pains and how they are affected physically and emotionally? I don’t think so. I just think many writers are trying to be politically correct, and write literature that would appeal to a lot of people. (The existence of social media where everything written is instantly posted to seek ‘likes’ doesn’t help in this respect.) In the process, I think many of us are not taking our roles seriously as thinkers, as the marginals, as those who ought to be daring enough to say what’s politically incorrect, and make people—our readers—shift uncomfortably in their seats, and encourage them to put into question all the dogmas and prejudices that they have embraced effortlessly. Writing about the growing pains of young girls is not a topic that would necessarily please most readers—as it would certainly make many shift uncomfortably in their seats, wondering why the author had to talk about such personal and private matters, or why he or she couldn’t have just stuck to a ‘pleasant’ topic. (People often say that to writers who write about sensitive matters.) What advice would you give to other writers looking to represent culture and faith within their fiction? Be daring. Take risks. Be politically incorrect, and by this, I mean you should go beyond just using unacceptable swear words. Trust me, it’s not enough. Do more than that. Go all the way. Write about that which will make people rethink what they’ve taken for granted. Eddie House Interview7/30/2020

So how does it feel to win a writing competition?

It’s amazing! ‘Breathe’ was written over a year before submission to OVO and had been rejected from previous publications. OVO was a ‘last chance’ attempt at submission before entirely scrapping the idea. To win first prize for a germ of an idea was overwhelming and really boosted my confidence in my writing ability. One of the main reasons ‘Breathe’ captivated us so much was the depth of its world-building. How did your vision of this dark future come together? During my own teenage years, dystopian stories were a massive part of YA literature (thanks to ‘The Hunger Games’ series). When writing ‘Breathe’ I was visualising Whittier, Alaska- the town that lives almost entirely as a community in a 14-story building as inspiration for the setting. ‘Breathe’ was almost entirely planned in my head and written in a couple of sittings. I wrote the parts I knew and the parts I couldn’t figure out or hadn’t considered were left for interpretation by readers – in a short story with a word limit, to spend too much time on world-building and explanation would detract from the actual story. Are there any particular dystopian authors, YA or otherwise, who you took inspiration from in the writing of this story? Ben Elton’s ‘Blind Faith’ was my first introduction to dystopian novels when I was 12. His world was filled with so many parallels to current media saturation, consumerism, and technology that it felt very “real” as to looking at how society would be on track to end up there. I wanted to reflect that in my writing as a “warning” to readers about the current climate in society. Your depiction of a corrupt health system and lack of adequate care for people in poverty carries a lot of real-world resonance. What made you want to tackle this very pressing issue? As mentioned above – we all know the current state of UK healthcare and the pressure the NHS is under is not sustainable. The idea of “birth debt” came from reading about the health care system in the USA. Just giving birth in a hospital there incurs thousands of dollars of debt. As with all dystopian stories, ‘Breathe’ comes with the underlying warning of “this could be reality if change does not happen fast”. Your narrator Bella is in love with Em, a girl with cystic fibrosis, while Bella herself suffers with anxiety. How did you handle the contrast of these two conditions with the common theme of breathing difficulties? I previously suffered debilitating panic attacks, which went largely ignored by those around me. There’s stigma surrounding both mental and physical health (especially with “invisible illnesses”) so that was in my mind when writing. I think mostly I just like the juxtaposition and parallels! It struck me that Bella’s feelings for Em would resonate not only with queer readers but asexual readers too. The lack of labels is refreshing. What do you hope readers take away from their relationship? Because “Breathe” is set in the future, it made sense to me that LGBT+ culture, language, and societal view would be completely different from how it is now. I deliberately didn’t touch on that explanation and left it for readers to infer if Bella keeping her feelings secret came from a fear of homophobia or simply fear of rejection. The “confession” of feelings is overshadowed by the life or death choices and Em’s feelings (either reciprocated or not) are not touched upon. I didn’t consider this from an asexual readers point of view when writing but I like that it was picked up on! I think the important thing to take away that I was trying to get across, is that this story was never about the romance. For Bella, retaining her friendship was far more important than having feelings reciprocated and I hope this demonstrates the importance of platonic relationships and how they hold just as much value as romantic ones. What advice would you give to other writers looking to intermingle important current issues with speculative and/or fantasy genres? Honestly, I don’t consider myself a reader of fantasy genres! I have a sociological background which is definitely reflected in everything I write. I’d advise to pay attention to the cultures and society around you. Make observations, question social norms, think critically. Most importantly, when deciding to interject certain topics into your writing, consider using personal accounts and anecdotal stories as research. This can be a good way to bring characters to life and make writing more realistic – even in a fantasy setting. What’s your next creative project? My main project at the moment is a full-length poetry book focused on teenage years with themes of sexism, mental health, and the pressure current teens are under. I’m aiming to have a final draft by November of this year. I do have ideas for another couple of horror themed YA stories (think zombies and paranormal experiences) but I’m waiting for the right time to work on them. My full-time job as a support worker takes up a huge amount of my time but writing is a hugely cathartic experience for me which I enjoy a lot. Tonia Markou Interview5/29/2020

One of the things that amazed us about ‘For Hugo’ was how it contained so many rich believable characters and relationships for such a short piece. What’s your process when it comes to crafting characters, both major and minor?

Thank you for the compliment! Characters are the heart and soul of every story, that’s why it’s crucial for me to get them right. I might have an unusual process when it comes to creating characters. When I start writing, I kind of become my characters. It’s similar to acting, which I have always been interested in. I take on a role and go with it. I imagine what this character would say and do in a certain situation. I round it all off by giving everyone something specific to differentiate them from the others. To me, it’s important that they have interesting personalities and traits, be it humor, a vivid detail, the way they speak and see the world, or vulnerability and flaws which make them human and relatable. I love writing dialogue since characters especially come alive while interacting with each other. It’s a fantastic opportunity to show what they’re made of, and I’m glad the result was convincing. Are you more of a meticulous plotter, or a seat-of-your-pants style writer? For short fiction I’m more of a pantser, as in I start writing and see where the sories and characters take me. I have a vague idea of what I want to convey, but that’s about it. I found that for flash fiction I write my best work when I don’t censor myself and just let the words flow. As far as longer fiction is concerned, I need some kind of road map to guide me, otherwise I might get lost and write myself into a corner, which means more work during the revising phase, which I don’t enjoy as much as the drafting or writing part. So I’d say I fall into the famous plantser category. Your narrator, Xander, is autistic, something you convey very authentically through his way of thinking. Do you have any personal experience with autistic teenagers and did you conduct any further research prior to writing this story? Thank you. My younger cousin in Greece has Asperger’s. He’s a sweet and very smart kid. I didn’t have any direct experience with autism before I met him for the first time eight years ago. He and his family were facing challenges due to misunderstandings in communication or misreading of emotions as well as prejudice that affected their everyday life. He inspired me to try my hand at a story with a neurodiverse protagonist. I knew it wouldn’t be easy to believably tackle a sensitive topic I didn’t have a lot of personal experience with. The more important it was to me to do my research, which involved reading many articles and personal accounts on the internet, and to post the draft to my online writing group for feedback. Your prose has a wonderful sense of humour. Is funny writing something that comes naturally for you, or do you have to work at it? I do consider myself a funny person, and I try to include humor in all of my stories if it fits the tone of course, so yes, I believe it comes naturally, especially in dialogue. Comic relief in fiction is something I enjoy to read. I suspect adding humor reflects my outlook on life in general, that despite all the negativity in this world, there’s also plenty of hope and joy. What other writers out there inspire and amaze you? Tough question, since there’s so much talent out there. I’m a big Stephen King and Joe Hill fan. Their characters are so well-rounded and Hill always comes up with such creative and imaginative plots. Other writers’ work I admire are Neal Shusterman, Brigid Kemmerer, Pierce Brown, Jandy Nelson, Lois Lowry and Laura Ruby, just to name a few. I loved Xander’s obsession with reptiles and the animal imagery you wove through his narration. What was your approach to the importance of pets in this piece? Animals are adorable, and the way characters, or people in general for that matter, treat their pets reveals a lot about their personalities. I wanted to explore different sides of Xander. We can see that he cares deeply for Hugo, we sense his affection for his pet lizard, but at the same time he struggles a little when it comes to social interaction with others. It was a nice contrast, showing that there are more sides to autism, that it’s not just black and white, but multifaceted and complex. Moreover, pets don’t discriminate. They accept you for who you are and love you unconditionally. At the end, Hugo brings Xander and his stepdad together, and he even succeeds in transforming an embittered Mr. Sakoulis. Being a polygot, how many different languages do you speak and how many languages do you use for creative writing? English is my third language. I was born to Greek parents in Germany, so I speak Greek, German and a little bit of Spanish and French. I used to write in German, especially poems as a teenager, and I have an unfinished fantasy novel I’d love to come back to at some point, but in my opinion English is a more flexible, more imaginative language, that’s why I chose to stick with it for my stories, even though writing in a foreign language definitely has its challenges. What’s next for you in the writing world? I’m currently editing my first YA novel. I want to get it ready for beta readers soon, then I can start the exciting and daunting querying process this year. In the meantime, I love distracting myself with flash and short fiction in various genres. Tonia is currently editing her first novel. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook and Medium at @toniawrites. The Player's Craft (Teaser)5/29/2020 In The Vagabond Stage by Kell Cowley, the reader is introduced to Timony, the new apprentice in Makaydees' travelling theatre. In the first of his picaresque adventures, Timony finds himself on a perilous journey through the Elizabethan underworld, at the same time as he is getting to grips with his role playing the leading ladies in the troupe's tragedies. In The Player's Craft, we catch up with Timony two years down the road. Now that he is confident in his acting ability and has embraced his female roles, we find that a conflict is brewing between the young star and his playwright master over the future aspirations of their company.

___________________________________________________________________________________ Scene Two (excerpt) “Your hair looks like a bird’s nest.” I ran a hand through my scraggly curls and it took a moment to pull my fingers loose again. When they came free they brought with them a cluster of twigs and dirt. Makaydees took a comb from his pocket and stroked its bristles like he were testing the sharpness of a blade. I shuffled over to the dreaded seat and he set about raking the comb through my long locks, ripping apart the tangles and wrenching at my scalp. “If I had a wig, I wouldn’t have to go through this torture every time,” I muttered, breaking the silence between us. “Real actors wear wigs, you know.” “And what is a real actor, pray?” “An actor who struts the boards of playhouses and palaces instead of roadsides. An actor who wears dresses with farthingales and furbelows, ruffs and puff sleeves. An actor who has fame, riches and roles that’ll be known through the ages.” Tears stung my eyes as I took another stroke of the comb. “Frills, frippery and empty poetry,” Makaydees retorted. ““Players such as that are nothing more than dolls for the rich to set dancing. Their only real talent is for sycophancy, making names for themselves through flattery. For whatever station it might earn them, their plays are worthless. There’s no life blood in licensed theatre these days. It all must be tamed to suit the sensibilities of the Puritans and Privy Council.” “You don’t know that!” I protested. “Tis over a decade gone since you left London. And the word on the road has it that the city is now home to the best actors and playwrights England has ever seen.” I twisted my neck to meet his stare. “Is that why you won’t go back there, Mak? Because you don’t want to face the competition?” I held the tears in my eyes a tantalising moment longer. I let them sparkle prettily before I blinked my lids and felt them slide down my cheeks. “Don’t take on so.” He clasped my chin and turned me away. “I’ll admit that our repertoire has become tired. What I need is time and peace to write a new play. And not just any play. The time has come for me to write my masterpiece before my mind dulls with age and my back can no longer hunch over parchment.” “I want to write it with you,” I dared to demand. “I write my plays for you. Be grateful my quill favours the female parts. No city playhouse would allow its boy players to take the leading roles like I do.” “But my girls never get to speak what they truly wish to say…and why can’t they ever live in the end?” “Because nobody lives in the end. I won’t sell our audiences any lies. Though I like to think your girls lend a little grace to our collective certain doom.” Makaydees ceased his brushing and stared pensively at his comb, now twined with the threads of my abused curls. He tapped my shoulder and nodded to the ladder in the wagon’s corner leading up to a poky crawl space where I made my bed. “Go,” he ordered. “Get your beauty sleep.” ___________________________________________________________________________________ The Players Craft will be released by Odd Voice Out later in 2020. The Vagabond Stage is available now in Kindle and Paperback form through our books page. Rowan James Curtis Interview4/24/2020

The Syrian refugee crisis is a woefully underrepresented event, both in the media and in fiction. For ‘Piano Wire’, what research and inspiration did you undertake to create this very moving tale?

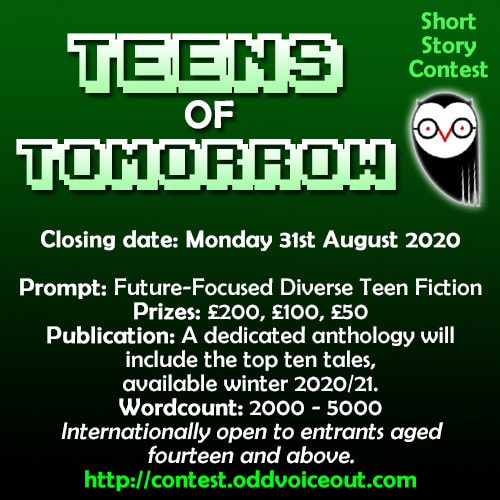

The inspiration for Piano Wire came from a moment which profoundly affected me emotionally. I was running an experiment in my lab whilst watching the BBC News reports of the battle of Aleppo in summer 2016. The reports from Syrian civilians who were caught in the middle of one of the bloodiest battles of recent history (which claimed over 30,000 lives) were devastating. The Professor I was working with came into the lab as I was watching a video call by a young girl trapped in Aleppo. It took me a few moments to compose myself before I could talk to him. From then on, I wanted the voices of the Syrian people to be heard in the west, but I was in no position to tell their story. Six months later, I met two Syrian students at the University of Surrey, who were both from Aleppo and who had come to the UK to study. It was only then, after listening to their own stories and memories of home, that I started to write. How long have you been writing, and is ‘Piano Wire’ part of your typical genre set? I’ve been writing for seven years now and I mainly write realistic fiction (although my first novel is an environmental fantasy adventure novel set on a coral reef and I’ve just finished a story about a talking dog). Most of my stories focus on real-world events and socio-economic injustices. The novel I’m currently working on is about dealing with loss, addiction, social immobility and class issues in the UK, and I often write stories which place my characters in vulnerable situations. These situations emphasise the human capacity to endure, find beauty in and even flourish in difficult circumstances. The first novel I wrote was essentially a self-help novel, with an environmental aspect to it and I believe mental health and climate change will be two of the most defining challenges my generation will face. I have confidence in the power of literature to educate readers about such issues, on personal and universal scales, but also as a medium for highlighting the beauty which is real and present within any situation, no matter how hopeless it may seem. The theme of musicians and the power of music is strong within this story. Can you tell us how that thematic choice came about? Music is a very big part of my life and all my stories have music and the arts as themes within them. But there are many reasons I use music within my stories. Firstly, for Piano Wire, I wanted people to see the Syrian war not just as a news story but as something which affected people who are just like them in appalling ways. What better way to plant the seeds of empathy and understanding in a story than a mutual appreciation of music between our characters and the reader? Secondly, I find you can learn a lot about any character by discovering what sort of music or art they might like, if any. When I start fleshing out a character, before writing, I always ask questions like, What would this person have for breakfast? What would they listen to on a Sunday morning, or on a day when someone close to them dies, or on the day a world war was over? What painting would they want to steal from the National Gallery, if they could? Would they like the work of a particular artist, musician or poet if someone introduced them to it? These sorts of questions help me to know a character before I write a word of their story. I feel music reflects the soul in a way that actions sometimes do not. I also find that showing what sort of music/art a person likes or dislikes is a very good way of teaching the reader something about a character in a ‘show the reader don’t tell them’ way. Thirdly, if we imagine a tune played by the right hand of a pianist, then whatever the left hand does changes the way we experience the tune of the right hand. Using this left-hand note as a backdrop, we can vary the feeling behind the right-hand tune from peace to tension, from joy to sadness. Now we can apply this notion to our writing. If we have a scene which ends with a character who is called to action, and we have our character hear the song ‘Here Comes the Sun’ by The Beatles on the radio, this will leave the reader with a totally different feeling to the same scene ending, than if they heard ‘Hello darkness my old friend’ from The Sound of Silence by Simon and Garfunkel. Thus, hearing and playing music is a useful way of providing motion, light and darkness in a story, and adding texture to it to make it feel multi-dimensional. What does a typical writing session look like for you? I go through periods of writing with the Graham Greene method, which is to try to write 500 words a day. But often, because I’m busy with planetary physics or music, I end up having mammoth writing sessions where I turn out ~8000 words in two to three days, whenever I have free time to do so. My favourite place to write is the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford, but I find myself writing pretty much anywhere there is silence. I’m one of these people who cannot write to music or anything else which may distract me, so I must be somewhere quiet. I also always write digitally, using my laptop, as I have all my ideas stored in a huge file called my ‘Mind Bible’ and prefer to be able to access my ideas using a search bar instead of trawling through hundreds of pieces of paper that I’ve spilled tea on. Oh, that’s another thing. Unless I’m in the Radcliffe Camera (no drinks allowed!), I almost always write with tea beside me. What inspired your decision to also include the perspective of an English teen in your story? This goes back to the idea of bridging the gap between the comfortable west (i.e. the boy in the UK) and the Syrian war. The Syrian People are not just numbers on a news story. They are real people with lives and loves just like the London teen watching the news. This is why I added the keyring to the story and is also why Rima ends up in London and the father of the house she arrives at is the surgeon of the English teen. These provide tangible connections between the characters. Liam’s almost banal experiences provide a Ying to Rima’s Yang within the story, and his chapter slows the pace before the ending, hopefully increasing the power of the last few paragraphs. ‘Piano Wire’ contains some beautifully penned but also quite stark and shocking images of real life war and conflict, which we don’t often see in YA fiction. Do you think it’s important that we should see more of this in future? As I mentioned earlier, it is important to portray the realities of situations, so we do not underreact to atrocities, or underappreciate good situations. Most of the young adults I know are very engaged in world events and have a strong sense of justice, which is sometimes diluted as our adult lives progress. Our world is theirs to inherit and I feel it is important for them to keep an eye on what’s happening in the ever-changing world. The news should report facts. But it is the job of writers and artists to engage young people in a longer lasting, emotional way, through fiction or other artistic devices. You have a Ted Talk on the importance of classical music. How do you bridge the gap between different artistic formats like music, public speaking and writing to get your message across? My messages are always consistent, no matter the form of communication. This is because day-to-day, I actively try to embody the things I believe in. This is part of who I am and is the root of all my creative endeavours. More practically, I try to use what I learn from different forms of expression, whether I’m doing public speaking, performing or writing, to help me improve in the others. When you consider the process of writing, it is author to page, page to reader. With music it is musician to instrument, instrument to listener. So, there is a barrier, or a medium which must be considered as part of the process. Both singing and public speaking and more direct processes, with a single step from person to listener. Each situation requires a different approach. For instance, I focus more on aesthetics when writing or playing instruments than I do when singing or public speaking. So that the spell isn’t broken. What’s next for you in the writing world? I write because I would find it impossible not to write, and will continue writing the stories I believe in, no matter what happens, whenever I get the time to. I write short stories at a rate of knots and hope to be featured in other competition anthologies over the coming months. However, my next real goal is to find an agent who will help me to find a publisher for the novel I’m currently writing, which is called Further Down the Vine. It tells the stories of two working-class families in Southampton, UK, and its major themes are addiction, social immobility and dealing with loss. I think this would be the first novel ever set primarily in Southampton. As is the case with Piano Wire, I would like to give a voice to working-class Sotonians, a group of people who have so far not been represented in literature. Global Mandatory Hibernation3/21/2020 Today was to be Odd Voice Out's first major presentation of 2020. We were all set to showcase our current titles and promote our newly published anthology collection at the Northern YA Literature Festival in Preston, together with pitching our small press to an audience of teachers and librarians. The event was officially postponed two weeks ago with organizers fearing that if they didn't cancel themselves, they'd soon be forced to. At the time, we still didn't quite believe the Covid-19 outbreak would cause so much societal shutdown in such a brief time. Yet here we are. Like everyone else in the world, we're struggling to adjust to the new normal and trying to adapt what we do to the limits imposed by the pandemic. Sadly we can no longer promote our wonderful 'Odd Voices' collection at the literary festivals, readings and gatherings that we'd been busily scheduling. But we're not going to let that stop us getting these stories out into the world. While it is going to take us all a hot minute to refocus our creative energies, we are already discovering many exciting ways that writers can continue to make their voices heard, even while locked indoors. After all, locking ourselves away in self-isolation is something we writers all do without our governments telling us to. And right now readers have never been more needful of stories. I have witnessed as much panic loaning from libraries, members exiting with heavy book bags, as I've seen from the supermarket hoarders. We'll do our best with the tools we have to left to get our anthology out to a readership who will value it. We'll also spend our quarantines deep in our writing caves, using our craft to make sense of what the world's become. We never planned it this way, but there couldn't have been a more fitting year for us to be running our 'Teens of Tomorrow' contest for our next YA anthology. As a wise teenager said to me only yesterday, we are now living through a moment in history and that has a way of waking you up. In my own cli-fi novel 'Shrinking Sinking Land' and its upcoming sequel 'Every Day Above Ground' I had my main characters, along with the rest of the world, go through a mass-sheltering period called the 'Global Mandatory Hibernation'. It's been startling to see a world-wide lockdown so similar to the one in my science fiction story, written just four years earlier. With our current future so uncertain, now more than ever we need writers to try and imagine what tomorrow will hold - for all of us, but especially the young. Please visit our contest page for details of where you can send your future-focused short stories. The deadline of August 31st is still a long way off, as it the end of the current crisis. We eagerly await your visions and voices.

Meet our New Odd Voices (Part 2)2/17/2020 It's Release Day eve! Time to meet the rest of our Odd Voices finalists. Stay tuned for more from our anthology authors as over the next few months we'll be releasing exclusive interviews giving them each the chance to discuss their own personal stories and writing processes. Until then, here they are in their own words! 'Breathe' author Eddie House (WINNING entry) Eddie House is a 23 year old genderqueer manic pixie daydream. They enjoy writing, roller skating, and complaining about writing. You can find more of their work at http://eddielhouse.tumblr.com, or in Anatolios Magazine. 'Love Makes Everyone (Into Poets)' author Oceania Chee (Finalist) Oceania Chee is worried about how she, a high school student with zero authorial credentials (as of right now, that is), looks next to the other authors in this anthology. Born in Japan to Malaysian parents, Oceania currently lives in Shanghai. When she isn’t writing, she can be found crying at Chinese films from the 90s, reading Manufacturing Consent for the nth time, or hiking to escape metropolitan life. 'Piano Wire' author Rowan James Curtis (Finalist) Rowan James Curtis spends his nine-to-five studying the Moon as a planetary physicist at Trinity College, University of Oxford. Aside from physics, he is a poet, an author of realistic fiction short stories and novels, a multi-instrumentalist and a big band vocalist. He engages in public speaking for causes he cares about, and he delivered a TEDx talk titled “Why we need Classical music” in March 2017. He is a devoted collector of first editions of good books, and he is currently half-way through writing his second novel – Further Down the Vine - based in Southampton, UK, about loss, addiction and social immobility. He is a tea lover, a dog lover and a lifelong supporter of Saints FC. Check him out at: rowanjamescurtis.com 'Oblivisci' author A.Rose (Finalist) A. Rose is a Creative Writing Graduate from UEA. Her work focuses on reframing disability, as well as the psychology of memories. She recently won first place in the Science me a Story 2019 competition, with her piece ‘The Nodes of Ranvier’. She is fascinated by myths and legends and loves writing about nature. She travels the world in a self-converted van with her fiancé and their Bedlington Whippet. Check her out at: www.write-a-rose.com 'Shoplifting' author Frances Copeland (Finalist)

Frances Copeland was inspired to write by the works she studied during her MA in English Literature, and she is particularly interested in creating characters who have been previously missed, or marginalized. Frances lives in Glasgow and likes loud punk rock. Her family wear earplugs. Meet our new Odd Voices! (Part One)1/21/2020 We are now just one month away from the release of our first anthology collection, showcasing the Top Ten entries of our 'Not So Normal Narrators' short story competition. So in these next two blog posts, we're letting our finalists introduce themselves in their own words. These talented writers have been a pleasure to work with and we can't wait to share their stories. But in the meantime, let's share a little about who they are and what they're about. Five more coming soon! 'For Hugo' author Tonia Markou (Second Place) Tonia Markou is a Greek-German polyglot and globetrotter with an unhealthy obsession for stationery, mugs, pajamas and Chuck Taylors. Her short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in 50-Word Stories, Dime Show Review, Youth Imagination, Corvid Queen and little somethings press. She’s currently editing her first novel. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook and Medium at @toniawrites. 'The Silence Rock' author Mary Ball Howkins (Third Place) Mary Ball Howkins uses her experiences as a wildlife volunteer in southern African countries to write stories that herald the daily successes of young Africans against difficult odds. These odds can be resistance to cultural change, snake bite, lions killing family livestock, drought, famine, and forced marriage, among others. She mostly focusses on rural village life while also setting stories in Cape Town and Nairobi. Mary Ball Is an art historian who has come to writing late in her career and after first volunteering in Namibia for desert-adapted elephants, then in Zimbabwe and South Africa, and after visiting other regions of Africa. She finds delight in the inventive language constructions Africans create when they speak English. Their language structures, a combination of their own dialect and English learned in school and conversation, often verge on splendid metaphor, figures of speech in which she takes great pleasure and adapts in her stories. Her goal as a writer is linked to her life-long role as educator. She hopes to inform non-African readers of all ages about the challenges African youth face in their villages. 'Size of Rice' author Sabah Carrim (Finalist) Sabah has authored two novels, namely Humeirah and Semi-Apes, both set in Mauritius where she was born. Her short stories have been shortlisted and published in various competitions organised internationally by Commonwealth Writers, Goethe Institute South Africa, and recently by the Bristol Short Story Prize. Her nonfiction was also a semi-finalist in the Gabriele Rico Challenge for Creative Nonfiction, and is scheduled for publication in an upcoming issue of Reed Magazine. Sabah was invited to be judge of the African Short Story Award, as well as to deliver the keynote speech on Cultural Stereotypes in African Literature at the African Writers Festival held in Nairobi in 2019. Sabah is also a law lecturer, and holds a PhD in Genocide Studies and Prevention, with a focus on the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge era. 'Imago' author Jack Bumby (Finalist) Jack is a writer living and working in Greater Manchester. He studied Creative Writing at Edge Hill University, during which time he won the LoveSexTravelMusik competition organised by author Rodge Glass, with his short story ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice?’. Since leaving university, he has placed second in a scriptwriting competition at Tyldesley Little Theatre and self-published a collection of short stories with fellow writers, titled ‘The Torment of Thomas Farriner’. Currently, he is an avid reviewer and spends a lot of time contributing to his blog, ‘My Creative Ramblings’. He is working on a novel and has recently begun a Master’s degree in Creative Writing. 'Anchor' author Colby Wren Fierek (Finalist)

Colby is a third-year student at the University of Worcester, currently attempting a degree in Creative Writing and Screenwriting. Living in rural Shropshire, they naturally like to write about unconventional family dynamics, inner-city class tensions, and contemporary queer teenagers being good and cool. Their favourite things include loud, terrible punk music and hideous pests like raccoons and possums. When they’re not writing, they like to acquire pointless musical trivia-their favourite Fun Fact being that former lead singer for The Vapors, Dave Fenton, now works as a solicitor for the Musicians Union. Their other Key Skill is being able to recall the location of every Jiggy from Rare’s 1998 platforming classic, Banjo-Kazooie (but not Banjo-Tooie. Please don’t ask them to do that). They’re even attempting narrative design for their own exploration, story-type game, about trains in the early 80s. They promise it’s a lot more interesting than it sounds. Their next big project is to start writing a historical novel centred around the lives of a group of working-class youths in 1970s London. You might’ve heard of one of them. Some kid called Todd Reynard. Who knows what happened to him? |